Cocaine: Colombia weighs a new aerial war on drugs

Tensions rise in Ecuador as election results roll in

11 Feb 2021

Colombia’s investment grade status at stake in tax battle

01 Mar 2021

Gideon Long in Caucasia, Colombia

On a hillside in northern Colombia, three dozen men in blue overalls toil through a field, destroying coca bushes. They work in pairs: one rams a hoe under the roots of a bush and levers it free; the other grabs the plant by its bright green leaves and wrenches it out of the ground. Ahead of them, sniffer dogs search for landmines. Around the field, heavily armed police officers stand guard in the sweltering heat.

“We can clear two and half hectares a day,” says Andrés Bautista as he pauses for breath and leans on his hoe. “Sometimes we have to walk for hours to get to them. At other times we have to stop while the mines are cleared. We live out here for weeks, sleeping in tents and hammocks.”

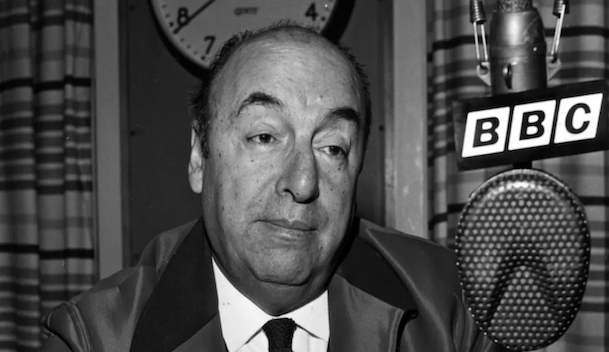

Backed by the US, in the 1990s and 2000s the state used crop-spraying planes to eradicate coca — the raw material for cocaine. But in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) said glyphosate — the active ingredient sprayed from the planes — was “probably carcinogenic for humans”. The government of Juan Manuel Santos immediately halted flights.